grad-, -grade, -gred, -gree, -gress

(Latin: walk, step, take steps, move around; walking or stepping)

Go to this Word A Day Revisited Index

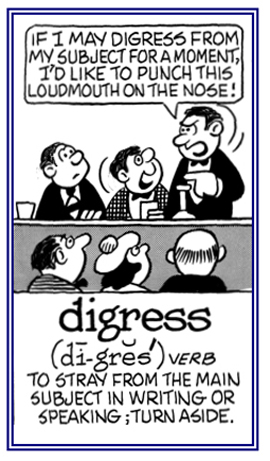

so you can see more of Mickey Bach's cartoons.

Forgive Ken if he seems to digress from our conversation, but he is concerned that his aunt's health will regress while she is hospitalized.

On TV, the political commentator was revealing the social and political digressions that the senator had committed while he was a member of the U.S. Congress.

Go to this Word A Day Revisited Index

so you can see more of Mickey Bach's cartoons.

A story that was going around some years ago, the source for which is now unknown, relates how P.T. Barnum was presenting a "freak" show in a tent. In those days, it cost each person five cents to wander around and gawk at the deformed people and animals.

It seemed that too many people stayed too long to look and there wasn't enough room for the new customers; so, Barnum had a sign set up next to one of the tent-flap exits saying, This way to the Egress.

Not knowing what an Egress was (or meant), the people would go through the door-type flap of the tent and they found themselves outside. If they wanted to go back in, then they had to pay the entrance fee again.

In an unrelated situation from that shown above, people were in a building where they noticed that the signs for INGRESS were printed in green but that the signs for the EGRESS were printed in red which might have made the meanings easier to understand.

2. A mutation of the body's repair mechanism causes fibrous tissue (including muscle, tendon, and ligament) to be ossified (turned into bone) when damaged.

In many cases they can cause joints to become permanently "frozen in place". The growths cannot be removed with surgery because such action causes the body to "repair" the area of surgery with more bone.

During years of development, as more bone grows and the patient loses mobility in more and more joints, it often becomes impossible for him or her to reach out, walk, eat, or even breathe.

The disease is usually fatal as the excessive bone structures crush the internal organs. People with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva usually lose all mobility by the age of 30 and die by the age of 40 and there still is no known cure.

FOP disease was so rare, no one wanted to deal with it

Dr. Fred Kaplan can't stop thinking about his kids. Daytime, nighttime, weekends. Their pictures cover his office walls; their smiles line the hallway of his lab at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in Philadelphia.

- Their letters ("Your the best Dr. in the howl wild wirld") hang next to his desk, displayed more proudly than any medical degree or award.

- Kaplan's kids are his patients, children with a rare and immobilizing disease called fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva.

- The first time he saw a child with FOP, says Kaplan, "it had the emotional impact of an atom bomb."

- FOP, which strikes roughly one in two million people worldwide, causes muscle and tendon to morph into hardened bone, imprisoning children in a second skeleton.

- The horror of the disorder—shoulders, hips and jaws fuse into locked positions—propels Kaplan's scientific mission.

- The children, whose average life span is 45, drive his devotion.

- Kaplan, 54, has spent more than 15 years unraveling the molecular and genetic blueprints of FOP.

- Early on, his colleagues told him he was wasting his time on a disease that afflicts fewer than 300 people in the United States, but Kaplan powered on.

- In April, 2006, Kaplan, along with his colleague Dr. Eileen Shore, his team at the University of Pennsylvania and international collaborators, found the key to the cause: they pinpointed a single gene mutation—one letter out of six billion in the human genome—that causes the runaway bone growth of FOP.

- Uncovering the "master key to the skeleton," as Kaplan calls it, could have dramatic implications.

- With a genetic target in hand, scientists may be able to design a drug that turns off the bone-growth switch in FOP.

- The discovery could also have an impact well beyond FOP, stopping the complication of extra bone growth after hip replacements or spinal-cord injuries.

- One day, says Kaplan, the skeleton key might even allow researchers to grow bone in a controlled way, helping people who suffer from osteoporosis or fractures that fail to heal.

- A rare disease? Yes, but as Kaplan suspected from the very beginning, one with universal applications.

- As of now, there is no cure for FOP, no way to stop the explosion of new bone, which is exacerbated by falls, bruises, injections, and surgery.

- Even today, few doctors know about the disease—close to 90 percent of patients are initially given incorrect diagnoses, including cancer.

- Medical help for FOP comes at no cost—Kaplan has never charged an FOP patient.

- "I find it unconscionable," he says. "Who else are they going to turn to?"

- Kaplan's salary comes from the university and an endowed chair; the majority of his research dollars are raised by FOP families at barbecues, golf tournaments, and garage sales.

- Last year's total: $1.2 million.

- Kaplan says he won't quit until there's an effective treatment and a cure.

"It was a compelling problem screaming for a solution," Dr. Kaplan said, and nobody else was helping to solve the problem.

2. The slope of a roadway, either up or down: The speed limit was reduced on the freeway due to the steep decending grade of 15 %.

3. The performance on an exam or test which is expressed by a number or letter; a score: On the final examination in English, Jill received an "A" which was the best grade possible.

The grade that Susan got on her biology test was 95%, which was very good, but 100% would have been a perfect grade.

4. A certain level of quality, intensity, value, or rank: The carpenter suggested that Jill use the finest grade of sandpaper on the table to make it very smooth before painting it.